The Oldest English Liturgy

The Book of Common Prayer is the oldest English liturgy in the world. The first Prayer Book was introduced in the spring of 1549 and was made mandatory in English churches as of Whitsunday of that year. In many ways this was the most momentous single event in English literary history.

The Authorized (or 「King James’」) Version of the Bible (1611) was not as singularly influential because it was itself only a step in the translation and dissemination of the English Bible. The Wycliffite (late 14th century), Tyndale, Great, Geneva, and Douai-Reims Bibles share its influence, and in many ways the literary distinction of the Authorized Version depends on the strengths of the Wycliffite and Tyndale versions.

Likewise, the literary influence of the English Bible was mediated to much of the English-speaking world through its place in Anglican worship. For centuries the Prayer Book made parts of the Bible particularly familiar and memorable. Even the great first folio of Shakespeare’s plays takes second place to the Prayer Book, because so much of the power of Shakespeare’s English is itself a product of the rhetoric and language of the Prayer Book.

A Foundation in Scripture

This first Prayer Book consisted of several kinds of material. The largest part of it is simply an English translation of portions of Scripture. The Psalter as a whole was not bound with the Prayer Book until 1662, but counting individual psalms assigned for liturgical use, the epistle and gospel lessons for Sundays and major feasts, sentences from Scripture (as prefaces for Morning and Evening Prayer, in the burial offices, etc.), the gospel canticles in the daily offices, and other uses and quotations of Scripture, the first Prayer Book was more than half a direct borrowing from Scripture.

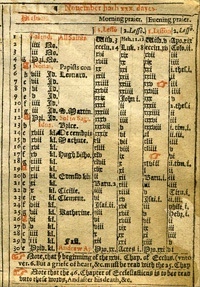

In addition the Prayer Book lectionary for Morning and Evening Prayer provided for the complete reading of the Bible during the Church year, chapter by chapter. Until after the Authorized Version in 1611, the Prayer Book used the Great Bible version of 1539, which was itself an edition by Miles Coverdale of the Tyndale Bible. Even then, however, the Prayer Book retained the Coverdale version in some of the most frequently read parts of Scripture such as the Comfortable Words and the psalms.

This use of Scripture is the first thing to note about the Prayer Book. The Bible is the Church’s book. The Prayer Book tradition, by its direct use of Scripture and by its arrangement for systematic reading of the whole Bible in daily offices, provides a proper context for reading and interpreting the Bible. The ancient Church read the Bible systematically in the lectio continua, the ‘continual reading’. In the Middle Ages this system became obscured by constant interruptions from innumerable feasts with their own proper lessons outside the systematic course. The Prayer Book lectionary restored the old pattern by longer readings and by eliminating most interruptions to the systematic pattern. By providing for the monthly reading of the whole of the Psalter, the Prayer Book also maintained the place of the psalms at the heart of the daily offices of prayer.

Elements of Continuity and Change

After direct use of Scripture, a second large section of material consists of English translations of traditional liturgical material. The Nicene, Apostles’, and Athanasian creeds were translated and given regular liturgical use. Hymns and canticles such as the Te Deum, the Gloria Patri, the Gloria in excelsis, the Sanctus, and the Agnus Dei were translated and maintained their traditional places in the Eucharist and daily offices. Dozens of collects and prayers were translated and also retained with little or no alteration. This conservative side of the Prayer Book can be seen also in the retention of traditional patterns and outlines for many rites and ceremonies.

So, for example, the 1549 Prayer Book maintained the same basic structure for the Eucharist that it had in the late medieval period. If the priest were conservative, his pre-1549 Latin Mass and his 1549 Prayer Book Mass would have seemed very similar to a person who knew neither Latin nor English. Of course the parishioners noticed the radical difference brought by an audible, vernacular liturgy. Still, the basic structure was similar.

In other cases, however, the Prayer Book altered traditional patterns of worship. One goal of the Prayer Book, when compared to earlier liturgical usage in England, is unity and simplicity. The unity consisted in suppressing the earlier variety of uses in England in favor of a single, mandatory rite for the whole country. The unity also consisted in combining the sometimes bewildering multiplicity of medieval liturgical books into one book.

The Prayer Book combined into one volume the brieviary (for the daily offices), missal (for the Mass rite), pontifical (for services peculiar to the bishop), and sacramentary (for baptism, matrimony, unction and other sacraments and sacramentals). This goal of unity in some degree reflected general late medieval and Reformation era trends. For instance, even before the English reformation there already was a move toward liturgical centralization in England. The Council of Trent later greatly centralized continental liturgical practice.

Simplicity came in the form of pruning of back the number of services. Where the medieval Church punctuated the day with offices of Matins and Lauds (in the middle of the night or very early morning), Prime (at daybreak), Terce, Sext, and None (at 9:00 a.m., noon, and 3:00 p.m.), Vespers (at dusk), and Compline (before bedtime), the Prayer Book established only two: Matins or Morning Prayer and Evensong or Evening Prayer. While this greatly reduced schedule might not be as adequate as the old for a religious community or for the extraordinary person of prayer, it was a much more sensible system for the parish clergy, whose primary job was to minister to their flock.

It also is a system in which the devout layman can easily join. Likewise the two Prayer Book offices dropped entirely variable antiphons and metrical hymns, and simplified the system for saying the psalms and for reading the lessons from Scripture. All of this meant simpler, briefer forms of worship, accessible to the layman, and useful for the average parish clergyman. This too, was a trend common in the era. The simplification of the daily offices and the increase in systematic Scripture reading in them were goals of the proposed breviary reform of Francisco Cardinal de Quiñones, published by Pope Paul III in 1535. The Quiñones breviary greatly influenced Cranmer’s work on the Prayer Book daily offices.

In both of these matters, however, it is notable that subsequent centuries have tended to reverse the tendency toward simplification. Most churches now, for instance, have hymnals which contain material for worship that varies from day to day and that mostly is not contained in the Prayer Book. The addition of metrical hymns to the Prayer Book tradition came from the direction of the Methodist world, and so constituted a kind of ‘Low Church’ supplement to the Prayer Book. Many other churches, particularly after the rise of the Oxford Movement in the 19th century, adopted the use of still other supplementary liturgical material in the form of breviaries, missals, and other such books. The Prayer Book forms the base, but the base historically has been added to by all Church parties after the rise of Wesleyan hymnody in the 18th century.

However, that is all later. In 1549 the first two goals clearly were to gather liturgical forms into one volume and to prune the medieval rites into simpler, less variable forms. These goals were theologically neutral and were perfectly in accord with the principles of the Catholic humanism that preceded the Reformation and that was represented in England by Erasmus, Dean Colet of St. Paul’s, Thomas More, and Henry VIII himself. Such ideas would not have been very controversial if the Reformation had not sharpened divisions, inflamed debate, and created on the one side a deadening conservatism and on the other a desire for change for its own sake. It is undeniable that the Prayer Book clearly marked a step away from medieval Catholicism. But then so did the Council of Trent.

The Prayer Book in the ACC

While the successor to the first Prayer Book, that of 1552, moved in a radically Protestant direction, after 1552 every subsequent Prayer Book reform has moved in the direction of 1549. Continuing this pattern, the Anglican Catholic Church now authorizes several editions of the Prayer Book, namely the 1549 English, the 1928 American, the 1954 South African, and the 1960s era Canadian and Indian editions. In addition, the Anglican Catholic Church authorizes the use of three missals (the English, the Anglican, and the American), the official Supplement to the Indian Prayer Book, a Manual for Priests, hymnals, and other liturgical works. While the Prayer Book in its several editions provides a literary standard for ACC worship and a core of common prayers and forms, the theological meaning of the Prayer Books, which was in flux for earlier Anglicans, has been firmly settled by other ACC formularies, most notably, The Affirmation of St. Louis.